Monster Curiosity Calculator

- Tools Used: C++, SQLite, Dear ImGui, Python

Role: Programmer & Designer

Team Size: 1 -

Itch.io Page

Demo Video

Repo Link

Monster Curiosity Calculator (MCC) is a database-driven statistics application developed to help answer niche questions about pocket-sized monsters. It uses a Python script to query an existing RESTful API, gathering all needed data into an easy to parse file. That data is then processed in a C++ application to generate a SQLite database that can be interacted with using a GUI developed using the Dear ImGui library.

Introduction

I've always had a desire to know obscure statistics regarding the places I am or the media I am interacting with. Frequently during my degree, for example, I would wonder at the average population of each floor of the library over the course of different days of the week (I wanted to be on the least populated floor).

As a lifelong fan of battling pocket-sized monsters, I have similarly wondered about the properties of arbitrary subsets of possible monsters. "If I created two groups, each containing only monsters of certain types, which would tend to be faster?" As such, when I began to develop my skillset at interacting with SQL databases the first thought that came to my mind was, "Perhaps I can use this to finally answer all those little questions that pop into my mind."

I decided to take this idea as an opportunity to experiment with a number of different libraries and languages, breaking the project up into the rough phases of data acquisition, database creation and interaction, and user interface development. The project began with a Python script that gathers all necessary data from an existing API, before transitioning to C++ development for creating the database environment as well as the interface users may use to interact with the database.

I continued to develop the functionality and ease-of-use of Monster Curiosity Calculator (MCC) until I felt I had achieved the goal I set out with: making a tool that allows calculating extremely niche and specific statistics about fictional monsters. To accomplish that goal, I gained knowledge on effective API querying, data processing, database usage, UI development, and designing flexible code systems.

API Querying

When beginning the development of MCC, I began by evaluating the data requirements of the task at hand. There are 1000+ monsters and I wished to support as much quantifiable information for each monster as possible (type, color, shape, abilities, etc.). Assuming a row per monster with a column per data field, I was envisioning a database of roughly 1000 rows by approximately 30 columns. Additionally, I wanted to generate an intermediate, human-readable file that would be dynamically converted into a database. This approach would allow me to more easily change the information gathered/processed and allow for database restoration in the event the database file was corrupted or lost.

This amount of data (30,000 cells at a conservative estimate), was beyond my capabilities to manually generate in any reasonable timeframe. Fortunately, during a previous project I had gained experience interacting with PokéAPI, a RESTful API with an intuitive and easy to process data structure. Knowing that the later parts of this project would take place in C++ (I had decided by this point to construct the eventual GUI in C++), I elected to create a script for querying the API in Python due to its easy to use networking libraries.

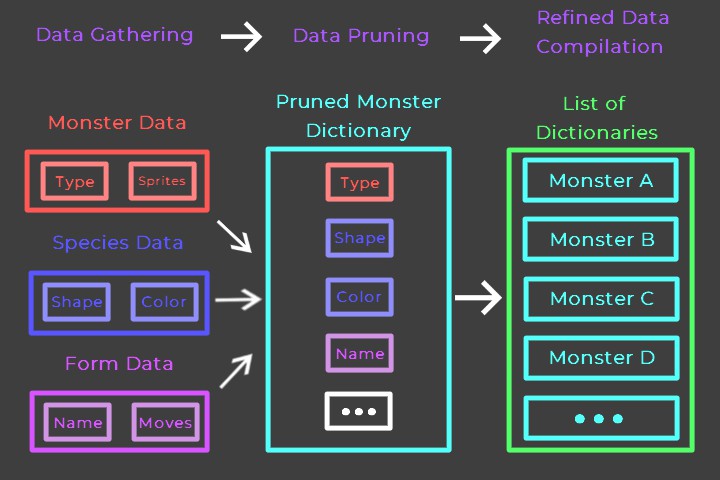

PokéAPI contains a truly massive amount of data, much of which is simply not pertinent to MCC. As such, the key purpose of the querying script was to identify the list of queries containing information I did require, obtain the data from those queries, and prune down and organize the obtained information to form a single file that could be processed to form my database.

-

- Entries gather all needed data, refine it down, and add themselves to a list of entries.

PokéAPI, I was able to retrieve a list of all monsters with query links to additional information for each monster. With this list I could construct a dictionary of information for each monster, ultimately combining all the entries together into a single JSON file. I chose to organize this file as a list of dictionaries, as this made the file easy to visually evaluate, making debugging errors quick, while also maintaining a connection between column names and values for easier database generation down the line.

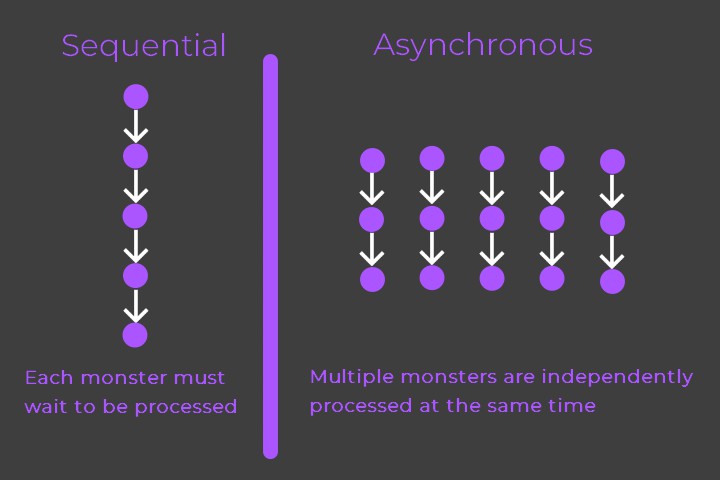

The data for a single monster is synthesized using information relating to that monster, its overall species, and its specific form. Due to this, generating the compiled information for 1000+ monsters requires more than 3000 queries. This number of requests, when processed in sequence, could lead to data gathering taking almost a minute. During the process of development, where I was frequently regathering data to fix bugs or add new data fields, this meant that I was spending significant amounts of time simply waiting for my data to compile.

-

- Monsters shouldn't have to wait for unrelated data querying.

Each final entry is, with only a few exceptions, formed using information entirely independent of any other final entry. As such, instead of processing each query in sequence it was possible to break them up into ~1000 asynchronous groups each containing only a few queries. Switching to this asynchronous request grouping drastically reduced the time needed to regather my data, reducing it to typically less than 10 seconds. As such, I had completed the first phase of MCC by developing a script that allowed me to quickly and easily gather the large amount of data needed for my database.

The Python script used for this section may be found in the project repository here.

Database Creation & Interaction

To contain and process the data generated by my Python script, I elected to utilize SQLite to form a database to serve as the heart of MCC. I chose to use SQLite as opposed to other SQL flavors due to its self-contained nature, lightweight size, and its well-documented C/C++ interface. These factors combined to make SQLite an ideal choice for my application devoted to processing static data without the need for a central remote database or server.

SQLite allows for the easy conversion of simple string data to SQL queries that can be efficiently evaluated in a number of ways. SQLite's statement preparation system works by outlining the statement fields before sanitizing and substituting in the specific statement values. As such, it is easy to dynamically build statements capable of handling a wide range of situations. During this project, I frequently used a pattern of creating string "formats" that I could combine in different arrangements to handle the data refinement and value calculation features that I wished to support. This approach naturally synergized with the similar tactic used by SQLite, meaning that developing database features was primarily an exercise in pattern deconstruction.

Beginning with table creation, table schemas are formed by a series of column specifications. As a typical schema has one row per column definition, I elected to develop a system wherein I could define an arbitrary list of column specifications where each entry contains information such as the name of the column, its data type, and any additional column arguments. This list is then converted to a single query that defines and populates a table using my previously gathered data. This system allowed me to maintain a large degree of flexibility, providing me the ability to easily modify the names and types of data processed as I iterated on the database and its source information.

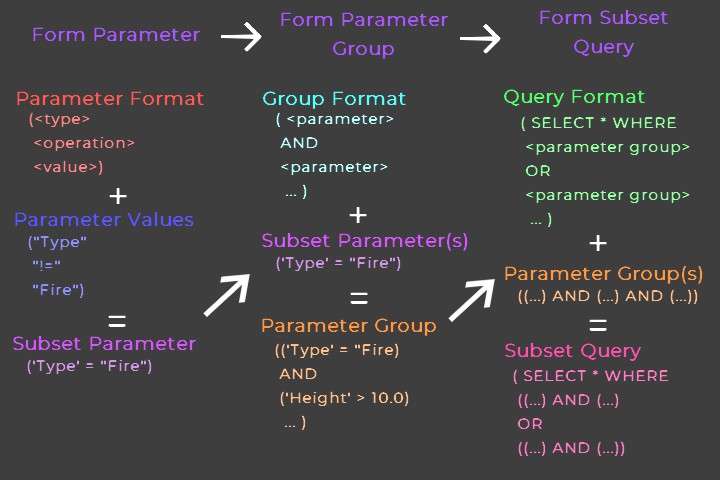

Moving now to interaction with created tables, I proceeded by breaking queries up into three primary components: types, operations, and values. A query to the database is typically in the form:

SELECT * WHERE (<type> <operation> <value>)

. For example, to retrieve all Fire type monsters, we could evaluate something similar to:

SELECT * WHERE ('type' = "Fire")

. In this instance, our type is, funnily enough, "Type", our operation is "=", and our value is "Fire". It is easy to create a generic pattern that can be used to form any equation of this type, allowing for the utilization of the format system mentioned above. Furthermore, while using this pattern each parameter can be evaluated as a separate logical argument, allowing for any amount of parameters to be combined to form a detailed set of criteria.

-

- The technique can be extended to combine parameters into groups for usage in queries that define data subsets.

With some slight modifications to this approach, it is also easy to define a system for calculating values derived from database data. Mutating the previous approach to something like :

SELECT operation(value)

, where 'operation()' is itself a format statement unique to each operation, we can achieve the same amount of uniformity and flexibility as with parameter definition. This approach, combined with SQLite's innate data cleaning while using the statement preparation system, allowed for the rapid formation of an easy to expand and secure system for defining and creating queries to the database.

Beyond these elements, the largest concern present was converting the raw database data to a prettier, user-facing format. To achieve this, I elected to use maps that were generated during the creation of each database "type". During type creation, when the list of possible values is being declared for the user to access, it was easy to add an additional stage linking raw values to the properly formatted "pretty" values. After a database query has been evaluated, the data, which is still associated with a column name, can be fed into the appropriate map to retrieve the data for use by the GUI.\

The C++ file primarily used for database interaction may be found in the project repository here.

User Interface Development

I utilized the Dear ImGui library to develop the interface for MCC in C++. I chose to use Dear ImGui because it is open-source, allows for the rapid creation of a functional user-interface with only C++ code, and is designed to have functional similarities to the style of frame management and rendering used in video game engines. This allowed me to utilize some of my existing knowledge of graphics and game development while minimizing the amount of additional languages and tools required to create a user-friendly interface for my application.

Additionally, as I learned over the course of utilizing the library, Dear ImGui is designed to be "self-documenting". Once downloaded, the library comes with an extensive demo which explores and explains the range of features included in the library. The link between any aspect of the demo and the corresponding code is extremely easy to find and the demo code is written to be as spatially-continuous as possible, meaning it is almost always intuitive to identify the code snippet responsible for an element and then dissect how that code works.

-

-

-

- Search the demo for a feature, find the related code, and then use that as the base for your own feature.

As such, learning and exploring Dear ImGui is a very hands-on, self-driven process. This, in my experience, leads to the development process with Dear ImGui being primarily defined by exploration, iteration, and curiosity in a way that many tools and libraries fail to be. Overall, the experience of getting to grips with Dear ImGui is more fun and engaging than many other interface development tools. As a result, I highly recommend Dear ImGui and plan to use it for future projects.

While Dear ImGui already handles much of the boiler-plate work required to establish a rendering environment (it helpfully includes examples of establishing a functional application for a wide range of rendering backends), there is still a small amount of "ugly code" that goes into creating an application with Dear ImGui. To better isolate generic Dear ImGui code from project-specific code, I elected to migrate all backend and application preparation to an "App" class. In essence, App defines functions to contain any required preparation for Dear ImGui while leaving open virtual functions for project-specific code. As such, for any project that utilizes Dear ImGui I can now simply bring in this app framework and create a child class of App to contain the code for drawing the UI of that specific project.

Armed with Dear ImGui's intuitive design patterns and a framework to make working with the library even easier, I fleshed out the interface for MCC by determining its core features and use-stages and creating a simple, independently functional window for each stage of program usage. After creating windows for dataset refinement, dataset viewing, and dataset value calculation, I simply had to create a structure to encapsulate and preserve data that needed to be communicated between windows.

Lessons Learned

During the course of developing MCC, I was able to tackle a large number of distinct challenges. The initial stages of the project allowed me to experiment with more efficiently querying APIs to gather required data, requiring an analysis of what queries could be optimized or changed to minimize unnecessary waiting. Following this, working with the SQLite C++ integration provided an opportunity to evaluate patterns in database queries in order to ensure queries could be formed flexibly while mitigating dangers such as unsanitized user input. Concluding the project by developing a user interface using Dear ImGui required mapping the connections between different phases of data processing and interaction in order to properly manage state and user input. By utilizing a range of tools and languages, I was able to deepen my understanding of topics such as API usage, database formation and interaction, and creating an interface to facilitate a better user experience.

While functional to my specifications, there are areas of MCC that are still ripe for improvement. To begin, the state management and overall code architecture of MCC warrant iteration. Furthermore, I wish to add additional features that felt unnecessary for an initial release that I nonetheless wish to eventually add.

In terms of state, the approach taken at time of writing is inelegant at best. A rather large and unwieldy "environment" struct is frequently passed about to allow various parts of the interface to share persistent state. I would enjoy dissecting this into multiple smaller, more regulated objects to make the overall flow of data in the program easier to track and modify. This combines with some lingering artifacts of the early development process to make the program more difficult to inspect and analyze than is desirable. Additionally, the amount of data generated at launch due to elements such as loading images and creating dynamic lists of values is sufficient to create a more in-depth initialization process that ensures initializing the program happens in an orderly fashion.

Regarding my desire for additional features, I plan to continue adding a number of quality-of-life features that will make my own experience using MCC more enjoyable. For example, allowing for the Subset Group Size display to toggle which subset groups are currently displayed is a planned addition. More ambitiously, I also plan to eventually allow for the user to define custom data columns and values. This would allow users to fully customize MCC to suit their own needs, providing the ability to track information specific to a user such as "have I caught this specific monster?"

MCC, overall, was a great learning experience and I look forward to applying the lessons it provided to the development of future projects and the continued development of MCC itself.

To potentially save you a trip to the top of this article, the repository for MCC may be found here.