Boba Eye

- Engine: Unity(C#)

Role: Programmer & Designer

Team Size: 2 -

Itch.io Page

Boba Eye is a casual game about making bubble drinks developed in Unity. During development, constructing systems that were data-driven and decoupled was a top priority. ScriptableObjects and Event Channels were two of the most important tools utilized to keep systems extensible and untangled. As an extra little treat, shaders helped to provide some visual flair and diversity to the primary gameplay task of making drinks! Ultimately, Boba Eye was a valuable experience that helped me gain insight into constructing a codebase capable of continual growth and adaptation.

Introduction

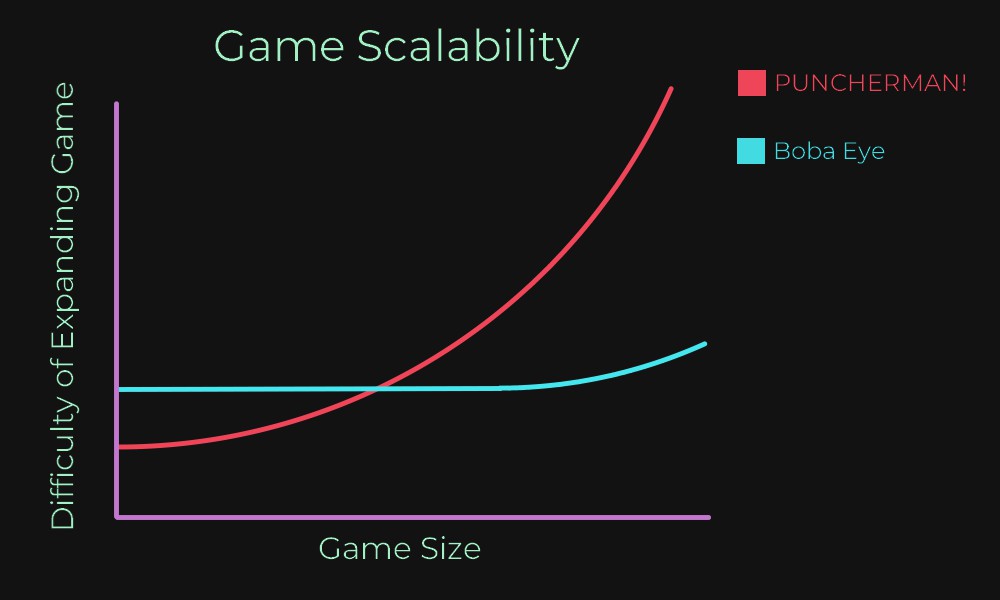

Reflecting on my experiences with previous development projects, namely PUNCHERMAN!, I began Boba Eye with one main directive: constructing a game that I could return to and develop over time. After navigating the rather large amount of tech debt PUNCHERMAN! accumulated during its first development cycle, I gained a renewed appreciation for the necessity of constructing systems that are durable, easily understood, and easily extended. Where we had spent months untangling messy, codependent systems to add new elements to PUNCHERMAN!, I wished to be able to occasionally return to Boba Eye and easily add in a new character or an additional component to the drink construction process.

-

- I wanted systems that, after an initially more complex development process, expedited future development.

In order to achieve this, I would need a project capable of being easily understood again after some time away. Forming systems that function independently, thus reducing the number of elements requiring direct manipulation at any time, would ease the process of re-learning the game's workings. Additionally, designing systems to be data-driven would allow me to make defining new game content largely a matter of creating new data to feed into existing, flexible systems. As such, the paradigms I followed to help achieve my ultimate goal of a long-term supportable game were decoupling and being data-driven.

With these core design principles in mind, I created documentation outlining the features and development roadmap of the game, noting which elements were absolutely essential and which would be nice to have someday. To construct systems adhering to my goals, I would need a strong understanding of what possibilities each system must be capable of handling and which systems would be in communication with each other. During PUNCHERMAN!, I learned how great the challenge can be to adapt a system to accommodate previously unconsidered possibilities. Thus, this early mapping of game systems, their interactions, and possible future additions would help to construct stronger systems capable of handling continued development.

Scriptable Objects

ScriptableObjects are a potentially unassuming feature of Unity that proved vital at developing systems that were more modular and data-driven.

ScriptableObject is, much like the more prevalent MonoBehaviour, a base class which scripts may inherit from in order to be easily utilized within the Unity editor. Similarly to a MonoBehaviour, ScriptableObjects are capable of containing state and functions that can be utilized by objects during a game's execution.

However, ScriptableObjects differ from MonoBehaviours in several crucial aspects. They do not share the same lifecycle as a MonoBehaviour and are not created as components of GameObjects. Instead, ScriptableObjects are created as assets which may be referenced by more standard GameObjects. As "assets", they are outside the standard scene-based lifecycle of most objects and are usable without requiring any explicit instantiation after their initial asset creation. As such, ScriptableObjects are able to serve as easily-accessible bundles of data and functions that do not need to be located within a currently active scene and are not tied to specific GameObject instances.

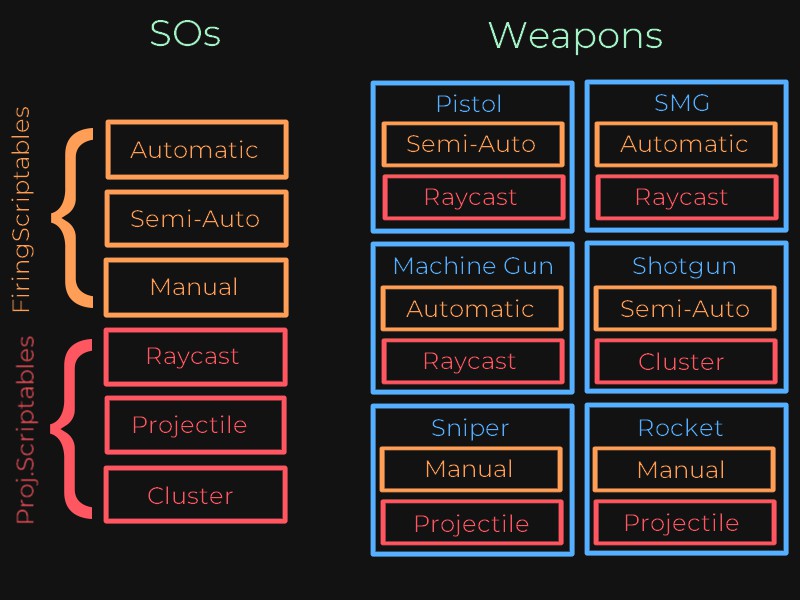

As an example of their potential usefulness, consider ScriptableObjects as they could be utilized as part of a game's weapon systems.

If designed with ScriptableObjects in mind, the class Weapon could expose the variables _firingSO and _projectileSO, each being references to ScriptableObject assets. The functions in Weapon may call functions and use data from the ScriptableObjects, using those implementations to guide their own behavior. In this way, FiringScriptable assets could be created that allow a weapon to fire automatically or semi-automatically. Similarly, certain ProjectileScriptable implementations could allow some weapons to fire projectiles using raycasts while others use physics projectiles.

public class Weapon : MonoBehaviour

{

[SerializeField] private FiringScriptable _firingSO;

[SerializeField] private ProjectileScriptable _projectileSO;

public bool TryToFireWeapon()

{

if(_firingSO.CanFire(WeaponState))

{

FireWeapon();

}

}

private void FireWeapon()

{

_projectileSO.LaunchProjectile(WeaponState);

}

}

public class FiringScriptable : ScriptableObject

{

public bool CanFire(WeaponState)

{

// code checking if the parameters should allow this weapon to fire

}

}

public class ProjectileScriptable : ScriptableObject

{

public void LaunchProjectile(WeaponState)

{

// code creating a projectile using parameters

}

}

In a situation such as this example, Weapon could be used to define a wide range of weapons by using different combinations of ScriptableObject assets to define aspects of the weapon's behavior. Furthermore, if, for example, all rocket-based weapons eventually need to switch to a different projectile, updating the ProjectileScriptable they reference will propagate those changes to all impacted Weapon instances. In this way, ScriptableObjects can improve the flow of development by creating systems that can easily combine reusable parts while allowing for those shared parts to be simultaneously updated across all usages.

-

- ScriptableObjects can be used as flexible building blocks for more complex objects.

Within Boba Eye, this general technique is used for defining data that may need to be shared by different instances of objects across scenes. For example, all flavors are defined as ScriptableObjects that contain information such as the name of the flavor and its color. Thus, I can create assets outlining each possible flavor and pass those assets to any GameObject that requires flavor information (such as drink particles). With this approach, I can easily define more flavors or alter the definition of existing flavors without having to manually update the related information across multiple locations.

ScriptableObjects are widely used across Boba Eye, also serving as the basis of systems such as customer definition, where a combination of ScriptableObjects defining the appearance, taste preferences, and speech patterns of a customer can be combined to easily create new cafe guests.

In this way, ScriptableObjects were a key component in creating maintainable, extensible game systems as they allowed me to develop frameworks which could be easily navigated to create new flavors, customers, and more. Returning to my overarching goal when developing this game, ScriptableObjects are an easy-to-use and convenient tool in Unity that promote a more data-driven approach to system design.

If you have not previously used them and are now curious, a Unity-provided explanation of beginning with ScriptableObjects may be found here.

Event Channels

Event-driven programming is a common and extremely useful paradigm when programming games and other user-driven pieces of software. Generally speaking, an event system allows for the creation of events that may be "fired" when certain conditions are met. These events often include data about the inciting incident, such as what object initiated it or when the event occured. Other objects then listen for events, each declaring what response it will make when it finally receives any events it is awaiting. This simple pattern allows for the creation of chains of functions to be called across objects without each object in the chain needing to know what consequences its own actions will have.

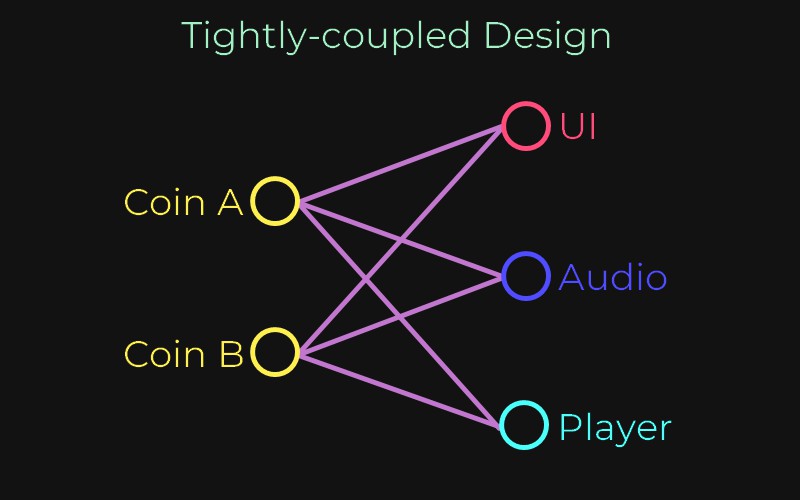

As an example, consider a scoring system in a game where the player obtains points every time they click a coin. In a direct, naive approach, this could be handled by letting coins know about the UI that shows the score. When clicked, a coin uses its reference to the UI and calls a function that increases the score and updates the UI.

While seemingly innocuous at first, this approach is ripe for the accumulation of tech debt due to its tightly-coupled nature. The coin needs to be directly aware of the UI and must tell the UI what to do. If eventually it is decided that collecting coins should also play a sound and cause another coin to spawn, suddenly a coin also requires direct knowledge of the systems for playing audio and spawning coins. As development continues and similar situations arise, this tightly-coupled approach will reduce flexibility and increase the likelihood of individual objects, like the coin, becoming bloated and unwieldy as they connect to more and more distinct systems.

-

- This architecture rapidly leads to a tangled web of connections.

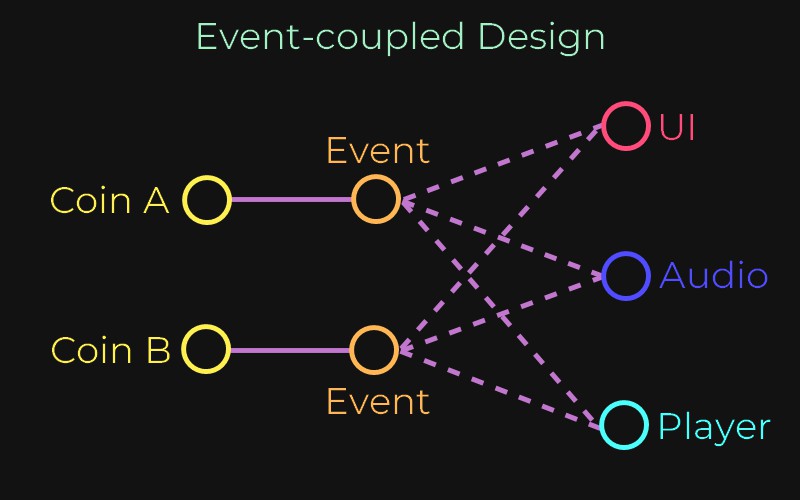

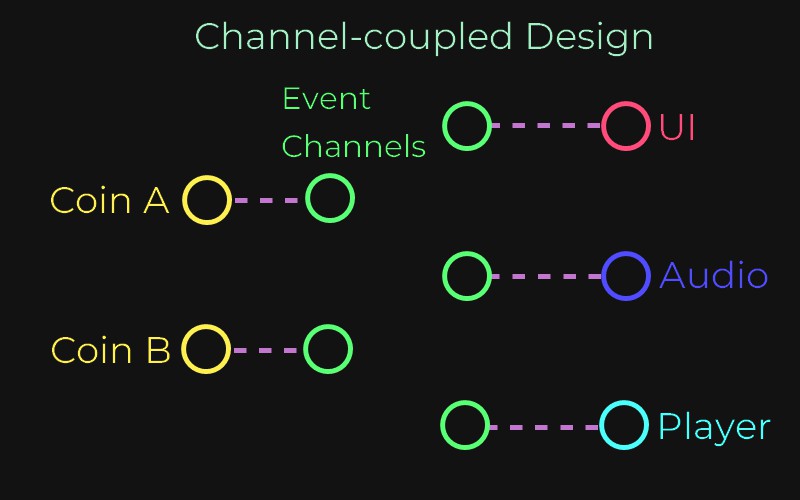

Designing the same system with an event-driven approach, each coin would instead fire an event when it is clicked. The UI, audio, and additional miscellaneous responses would all then be individually handled by the corresponding objects and systems, which would each listen for the event of a coin being collected. With this approach, adding any additional responses to a coin being collected does not require any direct modification to the coin itself. In this way, event-driven programming allows for the decoupling of systems and objects.

-

- Events help to prevent the coins from becoming dependent on other game systems.

There is, however, a question that technically-inclined readers may have considered: how do listeners gain knowledge of the specific events they are waiting for? There are a number of reasonable ways to provide event information to eager listeners, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Objects of certain types may be dynamically found and listened to, references to event broadcasting objects may be manually provided, events may be static members of their classes, and so on. Ultimately, however, a listener does need some way to know what events it is listening for.

Additionally, events require careful consideration of the lifecycles of involved objects and their listening patterns. If used wantonly, events can prohibit garbage collection from functioning at full efficiency by preserving otherwise useless data and can introduce difficult to dissect memory leaks and null exceptions by hiding references to non-existent objects and events.

Thankfully, ScriptableObjects can help to mitigate these potential weaknesses. ScriptableObjects are, just like any other object, capable of possessing and firing events. They are also, as mentioned previously, exempt from the standard lifecycle and scene restrictions of standard Unity GameObjects. These factors allow them to be utilized as "channels" for events.

An EventChannel is a ScriptableObject that contains an event that may be publicly listened to as well as a public function for firing that event. Due to its nature as an asset, as opposed to a GameObject instance in a scene, it does not need to "exist" in a scene to be referenced and used by objects in any scene. Any object that wishes to send a message along a channel can be given a reference to the desired channel and call its public firing function when in need of sending a message. Similarly, objects that want to listen for events along a channel can be given the channel reference without it being tied to any specific set of scene objects.

Utilizing ScriptableObjects like this, it is possible to create an event-driven system where objects do not need to be concerned with who may be sending or listening to events or whether anyone is even utilizing a given event channel. This decreases the burden placed on listeners to acquire event information while also removing the actual event launching code from broadcasters, allowing for easier decoration or modification of event functions.

-

- Channels make events safer and reduce the burden on broadcasters and listeners.

As a bonus, EventChannels also serve as an easy way to group related events into a single channel without needing to explicitly declare lists of objects or events that are related. Returning to the previous coin example, all coins could communicate in an EventChannel for coin collecting without the need for a shared static class event or a list of all coins waiting to be collected.

EventChannels also increase the safety of events by reducing the risk of firing or listening to non-existent events by connecting the events to objects that have a less volatile lifecycle. ScriptableObjects are always accessible during runtime, and will never be null if properly provided to an object. As a result, a coin will always be able to fire its event and a coin responder will always be able to listen for its event, regardless of if any other active objects are around to broadcast/receive the same event.

Within Boba Eye, EventChannels are used frequently to allow communication between objects from distinct systems that may wish to respond to one another. For example, the UI system for displaying characters and their dialogue lines is activated in response to an EventChannel that is fired when an occupied table is interacted with. The table has no knowledge of the UI; the UI has no knowledge of the table. They each only need to know of the EventChannel, which is a durable project asset capable of being easily provided in-editor.

Using this technique, ScriptableObjects are able to combine with event-driven programming to allow for even more flexible, safe decoupling. This, combined with the data-driven design of systems utilizing ScriptableObjects in a more standard manner, allows for the creation of gameplay systems that are easily extended and responsive without becoming brittle or codependent.

Unity has documentation explaining Event Channels here. Alternatively, one of their open projects, the repository for which may be found here, also demonstrates the concept in use.

Shaders

Shifting gears from scalable programming techniques, Boba Eye also required a scalable solution for generating visuals for player-created drinks. Due to its freeform system of allowing players to create drinks out of arbitrary flavor combinations, it wasn't feasible to create bespoke pieces of artwork for all the drinks the player could make. Instead, shaders (scripts capable of modifying how models or sprites are displayed in a rendering environment) were utilized to allow for drink visuals to synthesize authored and procedural elements in a way that ensured each drink was both visually enticing and distinct.

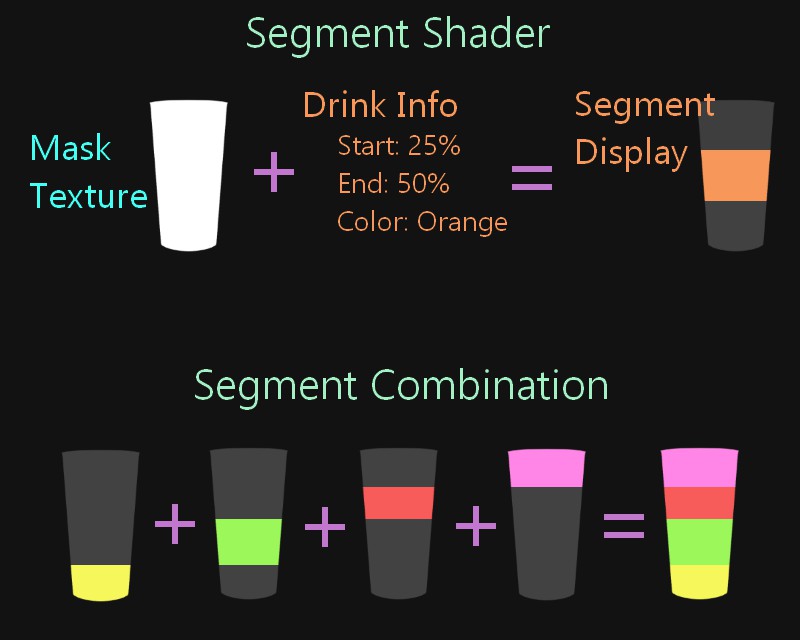

The least exciting, and yet most mechanically relevant, shader utilized by the drink system is that responsible for visualizing drinks being poured. As the player pours flavors into a drink, different colored segments will be created and stacked to display the amount of each flavor added to the drink. This is, primarily, a tool to allow players to visually interpret the ratio of different flavors in their drinks as they seek to fulfill the customer requirements.

This simple shader works by taking a texture matching the shape of the cup and using a "step" function to only display a specified segment of the entire texture. This segment is defined by two decimal numbers corresponding to the percent full the cup was before the flavor was added and the percent full the cup is with that flavor. These numbers are determined by a component on the cup that is responsible for coalescing the information of all drink particles taken in by the cup, which then communicates portions of that information to the segment shader in order to create appropriate color slices.

-

-

- The drink creates and layers segments for each component flavor.

Utilizing this approach, the player is presented with dynamic, cleanly colored segments that allow them to make more informed decisions regarding their drink creation. While not as visually interesting as some of the following shaders, it was essential to create a shader that allowed for effective communication of changing gameplay information to the player when constructing drinks.

Having been poured, drinks must be stirred up before being served. While only a transitional state for drinks, it was still important to ensure drinks are distinguishable while being stirred in order to help the player maintain their organization as they prepare different orders. Additionally, I wanted the drinks to communicate a sense of motion and action as they are stirred simply for the sake of making the process more exciting and fun. As such, I required a shader capable of maintaining the unique color of each flavor while also being dynamic and lively.

To achieve both of these goals, it felt best to find a simple technique for creating motion that could be applied to each flavor in the drink. For this reason, I turned to a good old-fashioned scrolling UV shader. UV coordinates, the values responsible for controlling how textures are applied to models or sprites, can be manipulated by shaders to give the appearance that the texture is "moving" across the surface it is applied to.

Using a technique similar to that described when creating flavor segments, the drink object communicates information to the shader about the amount of each flavor present within itself. The most dominant flavor is used as the background for the entire shader. Following this, additional flavors are each used to create a scrolling texture that is colored to match the corresponding flavor. The texture utilized for this has an appearance similar to streaks, allowing it to appear like segments of flavor rapidly swirling around the cup once the scrolling motion is applied.

-

-

-

- Individual layers are combined to create a composite stirring visual.

The cumulative effect is that the drink appears to be a base liquid (taken from the most common flavor) that contains many rapidly moving segments of additional ingredients. As each element of the shader is still simple and colored to match the flavor it represents, it is easy for the player to appraise what kind of flavors each stirring drink contains. As such, this shader serves as a good example of the way that simple effects can be combined and layered to create shaders that are versatile and reactive while maintaining visual clarity.

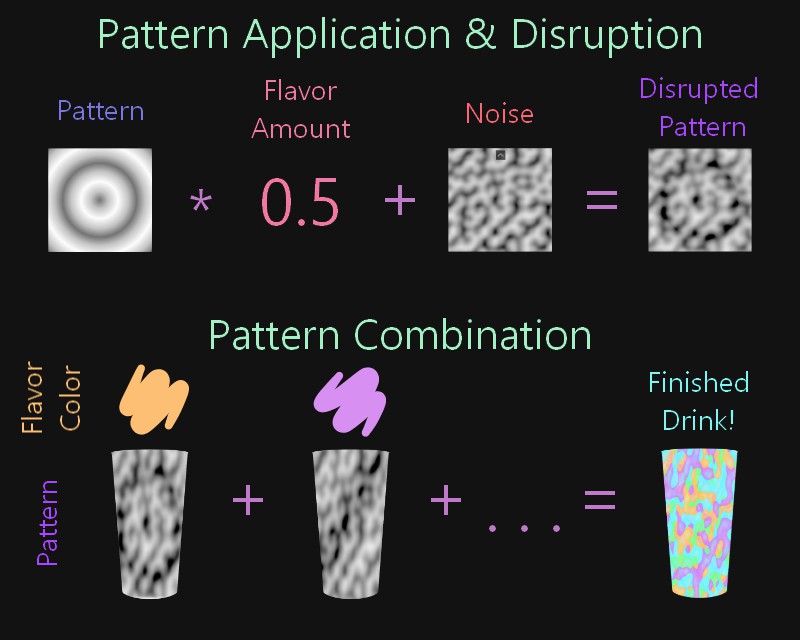

The most complex shader utilized within Boba Eye is, perhaps not too surprisingly, the one responsible for attempting to create unique, identifiable, and appealing visuals for an essentially infinite number of possible finished drinks. At the low-level, however, this shader shares many similarities with previous shaders in terms of layering individually simpler techniques to represent the multiple ingredients present in a drink. The fundamental idea of the finished drink shader is to create pockets of each flavor color that dynamically blend into each other in ways that appear cohesive and natural.

Much like the previous drink varieties, this shader begins by being supplied with flavor information by its host drink. Following this, each flavor is once again split off to do its own computations. Each flavor is randomly assigned a "pattern" representing its distribution within the cup, with the opacity of the texture corresponding to the "strength" of the flavor in a given area. However, because the patterns are structured and appear too artificial if used in their base state, noise is applied to each pattern in order to make the formation of each pattern more varied and mottled. This noise, which is slightly modified by the values of the connected flavor, helps to ensure that each flavor is distributed somewhat smoothly and unpredictably.

Each flavor having been applied to a noise-disrupted pattern, the shader now evaluates the flavor strengths at each location of the drink and arranges them in order of prevalence. Using this ordering, the color at a given drink location is determined by merging the colors of the strongest flavors at that location. In order to provide a more smooth transition between flavor colors and to provide more variety to the coloration of drinks, the overlapping colors are "interpolated" (smoothly merged between) using the difference in their respective strengths at that location.

At this point, the shader has constructed a warping, varied patchwork of colors that still clearly maintain the source colors of the component flavors. To complete the process, some finishing touches (such as applying a gentle "frost" tint to the overall image) are done to ensure the finished drink's appearance is pleasing, cohesive, and still readable. Thus, the shader is able to create a unique pattern of colors to represent any possible drink a player may try to make.

-

-

- This breakdown helps to visualize how each layer is formed before being combined.

Using shaders in this fashion allows for the dynamic creation of visuals to represent any arbitrary ingredient combination while maintaining crucial gameplay information. Thus, shaders, due to their ability to augment and enhance existing art assets, were an invaluable tool for navigating a situation where manually creating art for all possible gameplay situations simply wasn't possible.

-

- Each drink is always a little different!

Lessons Learned

Boba Eye was an excellent testing ground for experimenting with many techniques and design paradigms that I plan to continue utilizing as I progress development on it and other projects. By and large, it was a success in terms of creating systems that are more open to extension and modification than previous projects. I am pleased with the ways in which its systems facilitate the rapid, intuitive creation of additional content such as new customers and flavors. Furthermore, its utilization of ScriptableObjects and EventChannels helped to keep its systems decoupled and flexible, allowing for easier modification of systems to absorb new content and features.

However, that is not to say that all aspects of Boba Eye's development progressed flawlessly. There are three primary issues that arose during the development of Boba Eye: overengineering, managing distinct visual and physics layers, and navigating potential shortcomings of overreliance upon ScriptableObjects and events.

As with any programming project, Boba Eye was an exercise in properly planning interlocking systems while attempting to elegantly navigate any unforeseen shortcomings in those plans.

As mentioned, Boba Eye was heavily documented before it entered active development. Most of its systems were planned and outlined, detailing the possibilities they would need to accommodate and the connections they would have with related systems. However, in my attempt to design systems capable of handling as wide a range of inputs as possible, I failed to leverage some of my own authorial power to design constructive limitations into those systems. Additionally, in my pursuit of decoupling I occasionally connected elements, which by all rights should be allowed to function closely together, in fashions that engendered ambiguity and reduced clarity.

That is to say, I overengineered certain elements of Boba Eye. For example, the routine process of handling the player attempting to interact with an occupied table, at one time, involved a rather absurd chain of objects going , "Hey, I've been interacted with. Would anyone like to do anything about that?" that went far beyond the reasonable progression of table to party to contained customers.

Going forward, I plan to continue developing a better sense of the ideal balance between simplicity and flexibility for systems I design. In order to achieve this, I am improving my diligence with creating clear, subdivided development tasks that ask direct questions and receive direct answers. Instead of approaching a vague task such as, "Allow the player to speak to customers", I will instead tackle more concrete objectives like allowing a player to click on an object, allowing an object to activate a UI element, and allowing a dialogue line to be typed out. This, combined with improving my architecture planning by spending more time considering what reasonable limitations for a system should look like, will hopefully help me to avoid some of the overengineering I partook in during the creation of Boba Eye.

As a 2D game, Boba Eye involves a large number of different sprites interacting in a flat world, with layer order of those sprites being determined by what group and numerical value a given object is assigned. Particularly complex objects, such as cups containing drinks, involve many different layers for things such as the front of the cup, lines for measuring pour amounts, and the contents of the cup itself.

As these multifaceted objects are interacted with and moved around the game area, they must move behind and in front of other objects in a fashion that makes logical sense and communicates a sense of depth to the player. Maintaining this illusion in instances where the ordering of objects may be dynamic, such as ensuring held cups overlay cups merely sitting on the tray, or when different visual elements may appear or disappear, such as interfaces for dialogue, proved to be a fairly substantial challenge.

While a multitude of potential solutions to such problems exist, one that I shall specifically strive to internalize and extrapolate to similar instances is making better use of Unity's scene system. Unity is capable of additively loading different game scenes and environments, allowing for elements such as the UI and game world to be created and loaded independently. This allows for the construction and layering of each element to be simplified, allowing for clearer consideration of how to handle game elements that do require more complex layering solutions.

As a bonus, this greater division of game areas helps to promote a more productive consideration of which elements should and should not be in direct contact. In this way, this approach will also help to promote decoupling of systems from distinct scenes while reducing the potential for overengineering.

Lastly, there are, contrary to my prior glowing praise, some potential drawbacks to overreliance upon events and ScriptableObjects.

Events, as a natural consequence of their more decoupled nature, can prove more difficult to debug as time must be spent tracing the series of cascading reactions that events may initiate. They also require adequate foresight, as designing an event system that must later be updated to account for previously unconsidered information will involve editing all listeners of that event and can become prone to bloating.

ScriptableObjects, similarly, do possess some nuances that temper their immense utility. They can be, for one, somewhat deceptive with their durability. While they are more durable than a GameObject, they are still not entirely adequate for long-term storage of things like a save state. They are also prone to the methods of misuse that most centralizing design patterns can be. Similar to a singleton, they can, if used carelessly, lead to a proliferation of pseudo-global state as an easy solution to designing more complex channels of inter-object communication. Anecdotally, they also appear somewhat prone to corruption in certain Unity versions. It seems, in some instances, that the connection between the underlying script and the ScriptableObject asset can become disconnected, potentially losing the asset information.

Regardless, ScriptableObjects are still an incredible tool for Unity developers and I merely mention these points to ward off the idea that they are a panacea for poor software design.

While not mentioned elsewhere in the article due to not being a matter of technical discussion, Boba Eye has also allowed me to clarify and refine the methods I use to communicate with less technically-inclined teammates. Via creating requisition documents for art assets and communicating more clearly on asset creation and revision, I have accrued a greater appreciation of the constraints and factors important to properly utilizing an artist as part of a development team.

Ultimately, Boba Eye has been perhaps one of the most valuable projects I have undertaken. It has provided valuable insight into designing flexible, decoupled code systems, deepened my understanding of the balance between system simplicity and ability, and given me an opportunity to construct an extensible game base that I look forward to adding to periodically as I continue to grow as a developer.

Goodbye. See you next time!

Goodbye. See you next time!