Shadow Falls

- Engine: Unity(C#)

Role: Programmer & Designer

Team Size: 2 -

Itch.io Page

Demo Video

Shadow Falls was a jam game created over the course of two days for Texas Game Jam. During its rapid development, I deepened my understanding of ways to twist standard game development concepts to create novel gameplay systems. The focal point of the game was its award-winning shadow puzzle system, which applied everyday graphics techniques in inventive ways to facilitate unique gameplay. Beyond that, however, its failures in areas such as world design and player communication also provided valuable development insights about the need for balance between player freedom and direction.

Note

Many of the topics discussed in this article, and more, are also addressed in a postmortem I have previously written for the game on its itch.io page. If you wish to see another deconstruction of the lessons gleaned from the development of this project, feel free to read that post here.

Introduction

Shadow Falls was developed within a little over 48 hours for the Texas Game Jam, an annual game jam thrown by the game development organization at the University of Texas. The given theme for the jam was "negative space".

Almost immediately, my mind went to a "negative" that people are observing almost constantly: shadows. Being a perennial fan of the Resident Evil series, I was also reminded of a recurring puzzle type that I enjoy each time the series brings it back: the shadow puzzle. Being tasked with rotating an object in just the right fashion to create a specifically shaped shadow is an intuitive, viscerally satisfying gameplay system. However, I always wish to test new ground with any project I undertake so I was reluctant to simply copy over the classic formula of rotating a bizarrely shaped object to create a thematically-appropriate shadow.

Considering what I found compelling about the puzzles, however, left me with a question: why do they only ever use a single object? Of course, the answer, as with most things, is that it is much easier to set up a shadow puzzle that centers one carefully crafted object. All it takes is a little bit of vector math and, bam, you have a functioning shadow puzzle system where you rotate an object until it is in a desired orientation.

Confronted with this common limitation, I saw an avenue for exploration. If I could concoct a system that combined the satisfaction provided by the interplay of light and shadow inherent to these puzzles with a greater degree of player expression, I felt that could be a compelling gameplay hook. Armed with some knowledge from another project I was also undertaking at the time, I set out to explore the possibility of adding a new twist to this classic puzzle type.

Roughly two days and many hours of rapid work later, we had assembled an admittedly rough demonstration of this gameplay concept wrapped in a cute, pastel shell. However, it would seem that the idea holds some amount of water as Shadow Falls went on to win first place for its innovative technology (also winning first for its narrative, second for its visuals, and a judge's choice award).

With all of that in mind, let's spend some time digging into what worked and what didn't, focusing on the biggest points of success and failure for the game.

Shadow Puzzles

As previously mentioned, there are myriad resources and guides for constructing a standard, single-object shadow puzzle system. Traditionally, the shadows are, funnily enough, just smoke and mirrors. While the lighting elements of a traditional shadow puzzle serve to provide the player an idea of what orientation the object should be in, the true evaluation criteria is the orientation of the puzzle item. If the rotation of the object is close enough to a designer-chosen predefined value then that is a solution to the puzzle.

This approach, obviously, requires the designer to have pretty exact information about many aspects of the puzzle and its environment, such as what shape the item is and where it is relative to the light source for the puzzle. This need for a set of carefully controlled variables meant that the standard approach to constructing a shadow puzzle system was pretty much unusable if I was attempting to form a system that could accommodate any number of items in any number of configurations.

It is lucky, then, that I was tasked with assembling a basic ray tracer at roughly the same time that Shadow Falls was being developed. While I considered multiple different ways to evaluate the collective shadow cast by a group of objects, including converting the shadowed surface to a texture to be evaluated per-pixel or even using shape recognition, they all seemed prone to one error or another. Instead, I figured why not just leverage a concept I was already experimenting with: casting rays.

-

-

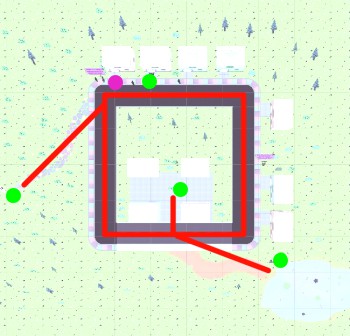

- The rays are able to approximate the shadow cast by an object, even at a rough grain.

I began by forming a system wherein an array of objects could, in tandem, check for an obstacle between them and a defined lightsource, mirroring an implementation of a direct shadow system from a graphics ray tracer. From there I simply had to allow for each "checker node" to indicate whether it was wanting to be obstructed or not, allowing me to define a desired shape for the obstructed areas. At that point, I had a basic version of a system that could evaluate whether a specified "shape", defined by a set of individual points, was being obstructed from a light source.

-

-

- Combining simple shapes lets the player freely craft complex shadows.

This approach, which relied only on the ability to cast a ray from one object to another, meant that any item could be used to solve a puzzle as long as it was properly configured within the collision system. Additionally, the number, size, and shape of the items casting shadows was completely inconsequential. Thus, the promise of a shadow puzzle system that allowed the player to use any number of items in any number of positions they wanted was fulfilled.

However, there are a few major flaws inherent to this system. Firstly, it can be expensive. If you want a more accurate approximation of the actual shadow cast by an object then more rays must be cast, directly tying the precision of the system to how much time it takes. Additionally, and this is likely obvious if you ever see the puzzle designs in the game, it is a system most suited to evaluating shadows composed of rigid, orthogonal lines. Introducing curved shadows increases the chances of the actual shadow cast by an object being interpreted differently from the rays checking for an obstruction. It is, of course, possible to decrease the constraints imposed by this fact by casting a more extensive grid of rays, but that once again raises concerns of performance.

There are, however, ways to mitigate these issues to some degree. Regarding the performance issues, being selective with when and how the rays are cast can reduce the overall performance cost of casting so many rays. For example, in the game rays are only checked for a single frame once a player requests an evaluation of their puzzle.

An alternative approach would be to amortize out the cost of checking rays by asynchronously checking different segments of the puzzle at different points in time. This would prevent the raycasting from introducing sharp performance drops every time they are evaluated, and would lead to a system that feels more dynamic and responsive as it could respond to the player over time without the need for constant requests for appraisal.

Beyond performance concerns, without adequate tools this system is just painful to use. Having no time to develop a more formalized pipeline for creating puzzles, I had to take an extremely primitive approach to constructing the puzzles seen in this version of the game. For this jam I went in for each puzzle, created around 100 checker nodes, and manually positioned and set the desired value for each one.

This is, as mentioned, an issue of tools. Ideally, a designer would be able to provide the puzzle guide image to a system that parses it to determine which segments should be shadowed or lit. From there, they should be able to indicate the physical bounds of the puzzle area and the desired resolution of the ray checking, removing the need to painstakingly chisel the puzzle parameters into virtual stone.

In spite of these issues, people liked the system. It met the basic goal of letting people make shadows with any items they wanted, which is compelling enough to fill a small jam game. Nobody caught on to the fact that, once again, the actual shadows were little more than a visual aid for the actual underlying functionality (though in this instance the underlying functionality is pretty much the same concept).

I, for my part, am pleased with having crafted a system that did exactly what I wanted it to do, with only manageable drawbacks, using reapplied basic concepts. As time goes on, I gain an appreciation for the fact that most every mechanic in games, when you truly get down it, is a basic concept reapplied in a novel way to make something interesting.

World Design

Moving now to perhaps the greatest failure point of Shadow Falls: its world design. The world design of Shadow Falls serves as a microcosm of many of the design issues that held the game back in spite of its better ideas. Simply put: it doesn't help the player have fun. Many players were left stumbling around a relatively barren, if pretty, world trying to find where exactly we had hidden the fun stuff.

-

- If I removed the magenta dot, could you determine where the game started?

The image above shows an annotated aerial view of the game world. The magenta dot indicates the player spawn, lime dots indicate the location of puzzles, and the red lines indicate the visible pathways in the world.

Upon seeing this image, something immediately becomes apparent: this world has no direction. If I removed the magenta dot, there is nothing in the construction of the surrounding area and its pathways that would lead one to conclude the game starts there. Additionally, the puzzles do not seem to be arranged in any fashion that provides the player an idea of which order to tackle them in. Beyond the spatial clue of the easiest puzzle being directly by the spawn, every puzzle may as well have been randomly placed. Finally, the cyclical nature of the central pathway removes any sense direction or progression from exploration, an issue only deepened by the way in which offshooting paths fail to reinforce any sort of structure.

When designing this world layout, I was attempting to provide the player a "free" and "unpressured" experience. However, in my uncritical attempts to do so I wound up making a world that is not designed to be navigated in a fun, intuitive way. In the time since the development of Shadow Falls, I have come to appreciate the ways in which adding some degree of structure and linearity can serve to augment and strengthen the sense of freedom provided by a game. If, instead of giving the player full freedom from the start of the game, I had placed them in a linear area that opened up into a freeform experience, then I am sure many more players would have walked away happy and feeling a sense of agency.

-

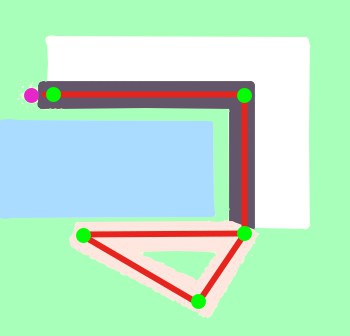

- A mixture of linearity and freedom leads to more parsable, navigable game worlds.

If we consult this second (unfortunately more ugly) map then we can begin to imagine ways that Shadow Falls could have been structured to better accommodate a mixture of player direction and exploration. On this version of the map, geographical features, such as the lake, can be used to constrain the play space in a way that feels inoffensive. Thus, the designer can be certain where the player is actually going as they play the opening stretch of the game. Once the player has been properly introduced to the game and its mechanics they can be given choices, as seen in the triangle of puzzles at the southern end of the map. After the player has made a choice, the world then provides a way for the player to navigate back towards the path they did not travel by connecting to it with a new, enticing path for the player to explore.

While relatively simple and ripe for further improvement, a world designed in this way is much more understandable from both a designer and player perspective. A designer is able to have some degree of confidence in the order the player will progress through the game world while still facilitating player choice. Meanwhile, the player will, despite technically having less freedom, likely feel more engaged by the freedom they are later given as they have been placed in a space that wants to be explored and provides them the information to effectively do so.

As stated at the beginning of this section, my initial, lacking approach to player communication and freedom extends to other areas of the game, such as the tutorializing of the puzzle mechanics. As in this case, many of these related issues could be solved by a stronger balance between player agency and intentional design. In all, the failures of the world design of Shadow Falls serve as a good lesson in the ways that linearity and openness must be managed in all aspects of development.

Lessons Learned

Having now deconstructed key points of success and failure for Shadow Falls, it becomes clear that both provide insight into creating engaging, player-driven experiences.

On one hand, the success of the shadow puzzle system professes the virtue of crafting unique systems that facilitate player choice by compositing individually simple, standard concepts into a larger whole. By evaluating an existing style of gameplay that I found compelling, noting an avenue for expansion, and drawing from experience in another area I was able to execute on an idea extremely quickly and effectively.

Contrasting that success, one can observe the equally instructional missteps regarding the world design of the game. Mirroring general trends in the lackluster player communication of Shadow Falls, an overly naive, open approach to world design left players without adequate guidance to truly enjoy the game. Rather than simply throwing players into the deep end (while a potentially valid approach for a game not seeking to be primarily relaxing), a better decision would have been to slowly layer freedom and player choice onto a stronger foundation of game knowledge built during an initial period of linearity and stability.

Overall, both lessons point to the importance of composition when creating anything of greater complexity. Looking for ways to leverage existing knowledge, be it from a developer or player, allows for one to more confidently build towards something novel and engaging. It could be said, if one was feeling poetic, that the lessons of Shadow Falls' development are much the same as the lessons contained within its defining gameplay system.